There are periods in life when you somehow know that you’re in the middle of something grand and world-altering. If you’re of a certain vintage, you’ll remember feeling that something was in the air musically when the calendar ticked over to 1991.

World events had a lot to do with it. Optimism was high as the Soviet Union was melting away and would be gone by the end of 1991, two years after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Nelson Mandela was finally out of prison. And although most of us weren’t aware of it yet, the foundations of the World Wide Web had been laid.

On the other hand that year, there was a brutal worldwide recession, the hangover from the first Gulf War, and the beginnings of fighting in the Balkans which would last until the end of the decade.

There was also a dramatic demographic shift as Generation X, the children of the Baby Boomers, started to come of age. Although highly educated, the recession left them under-employed and fearful that they’d be the first generation in years not to achieve a standard of living better than their parents. This cohort was cynical and more than a little scared about their prospects. This is where music came in.

Hair metal dominated the latter part of the 1980s along with a re-framing of older artists as “classic rock.” Gen X had no interest in either. The hedonism of hair metal seemed out of step with the economic, social, and political conditions of the time. Besides, hair metal had played itself out, having devolved into an endless parade of mid-tier bands hawking mediocre power ballads. Meanwhile, the classic rock artists were seen as dinosaurs, relics from another time and whose music did not speak to this new generation of music fans.

By 1991, Gen X started to exert its power and influence on the music industry, especially after the American recorded music industry adopted SoundScan, a super-exact way of counting the number of records sold. Instead of relying on dodgy estimates on what albums were selling by record store people, SoundScan counted records and CDs one-by-one at the cash register.

When the new system kicked in after March 1, 1991, it became obvious that the sales of certain genres were being hideously undercounted. Country was a much, much bigger deal than previously thought. And so was alternative rock, a genre that had been seriously underestimated for years.

Once confronted with the raw numbers, the recorded music industry pivoted, shovelling more money and promotion into the development and marketing of both country and alt-rock acts. That year saw the release of an incredible of landmark albums: R.E.M.’s Out of Time (March 12), Gish from the Smashing Pumpkins (May 25), Pearl Jam’s debut, Ten (Aug. 27), Nevermind from Nirvana, Bloodsugarsexmagick by the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Primal Scream and Screamadelica, and Tromp Le Monde from the Pixies (all on Sept. 24), Soundgarden’s Rusty Cage (Oct. 8) and Achtung Baby from U2 (Nov. 19).

Add in the first Lollapalooza Festival that summer, and it was obvious that the times, they were a-changin’.

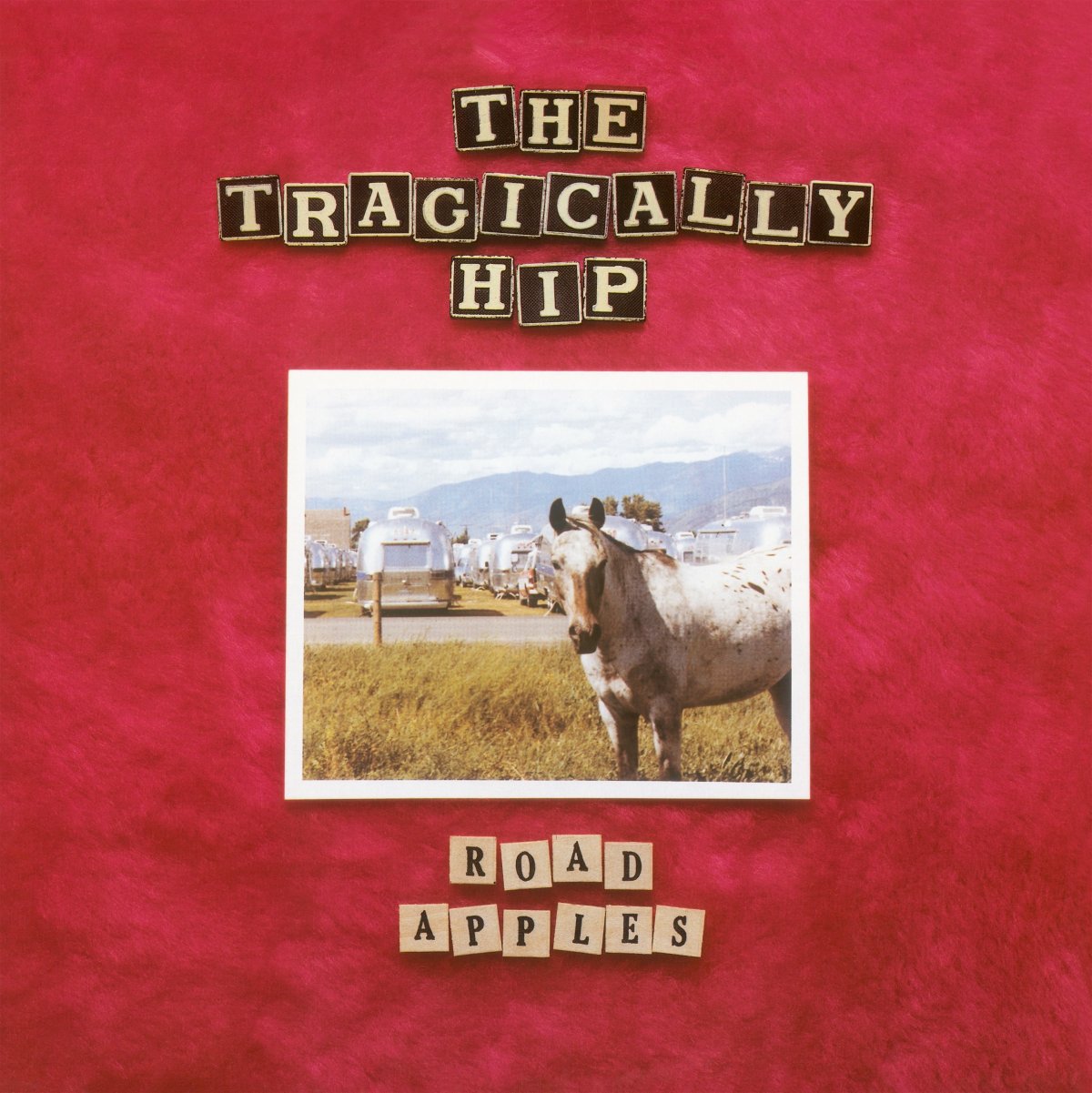

Overlooked by the world outside of Canada was that this parade of now-classic albums really began on Feb. 19, when the Tragically Hip released Road Apples, their second full album. The Hip’s story really began with the Up to Here album in 1989, a record that showed astonishing maturity and promise. Over the next two years, the band’s popularity rocketed, coinciding with Canadian Gen Xer’s growing need to have music that reflected their values, beliefs, wants, aspirations, fears, and anger. They wanted music made by their peers.

Those demands were a long time coming. When the Canadian content rules for radio were enacted 20 years earlier on Jan. 18, 1971 — the laws that required Canadian radio stations to devote 30 per cent of their playlists to Canadian music — they were met with derision and ridicule. Everyone knew that Canadian music was inferior to what was coming out of the U.S. and the U.K. Now you want to feed Canadians a steady diet of bad music?

It was rough, but it was necessary. Before 1971, there was no Canadian music industry to speak of. The CanCon rules set in motion not just a cultural protection strategy but an industrial one. By creating this artificial demand for Canadian music on the radio, that meant creating an industry to feed that demand: record labels, recording studios, producers, engineers, managers, agents, promoters, venues. It took until 1991 before we began to see widespread major benefits from those policies.

Everything about Canadian music improved. And the Gen Xers were there to embrace it.

The Hip was the right band at the right time. They became the foundation of what has become known as the CanRock Revolution of the ’90s, a period when Gen X embraced its musical nationalism. Over the next few years, there was a massive explosion in the popularity of Canadian bands: The Tea Party, Tom Cochrane, I Mother Earth, Matt Good, Our Lady Peace, Barenaked Ladies, Sloan, The Watchmen, Moist, The Headstones, Econoline Crush, Rheostatics, Bif Naked, Pursuit of Happiness, and so many more.

Again, though, we need to go back to Feb. 19, 1991, and the release of Road Apples. After such a strong debut, the anticipation for the album was intense. And the band delivered.

Decamping to New Orleans to record, the album was supposed to have been called Saskadelphia, a title that was rejected by their American label. As a middle finger, the band declared, “This is really horses–t! So we’re going to call it Road Apples.” Their U.S. label, apparently unaware of Canadian barnyard colloquialisms, signed off. (Three months after the release, radio programmers received special acrylicized actual road apples. Imagine the record promo person tasked with making that happen.)

The album would become The Hip’s first number one record, selling its first 100,000 copies in just 10 days (It would eventually sell more than a million, earning it the rare and coveted Diamond status in Canada). And it was loaded with Canadiana.

The first single, Little Bones, was named after a cat in a book called Last of the Crazy People by Canadian novelist Tim Findley. Fiddler’s Green (which they almost never played live until two decades later) took its name from an area southwest of Hamilton. Three Pistols refers to Trois-Pistoles, Que., and is about Group of Seven painter Tom Thompson. There was a long list of singles on Canadian radio, including Twist My Arm, Long Time Running, and Cordelia.

By the end of the year, the band had toured with everyone from Lenny Kravitz and Living Colour to The Happy Mondays and Joe Jackson. They covered the country, the U.S., and even parts of Europe with the highlight being an appearance at the Pink Pop Festival in Landgraaf, The Netherlands.

In keeping with such an important release, the band has released a special 30th-anniversary edition of Road Apples. While there are no extras on this release, it does offer fans a chance to get caught up. However, the band has been going through the archives and has found material from that era that will inevitably find its way into the marketplace. Stand by for that.

Years like 1991 don’t come along very often. But when they do, they hit with the force of a tsunami. And let’s give The Hip their due for what they helped make happen.

—

Alan Cross is a broadcaster with Q107 and 102.1 the Edge and a commentator for Global News.

Subscribe to Alan’s Ongoing History of New Music Podcast now on Apple Podcast or Google Play

© 2021 Global News, a division of Corus Entertainment Inc.