Back when The Simpsons still offered biting social commentary, season seven saw Homer try to impress Bart and Lisa by scoring tickets to the Lollapalooza-like Hullabalooza, which featured Smashing Pumpkins, Sonic Youth, and a very baked Cypress Hill.

Homer was crushed when he realized that his music, which he had always believed achieved perfection in 1974, wasn’t cool anymore. He’d become just like this father.

If you’re a Boomer, you know exactly how Homer felt. The music you grew up with had grown old, morphing from vital, zeitgeist-capturing sounds into something the world was now calling classic or, heaven forbid, oldies. This also meant that you were now old.

Today, just like Homer, Gen X is enduring a painful truth. Their music is now old. And so are they. How could this have possibly happened?

This requires a little insight into how the radio industry works.

In North America, commercial music-based radio stations present themselves by promising to provide a specific type of programming. If you want, say, the biggest pop hits of the day playing nonstop, you go to your town’s CHR station, (Contemporary Hit Radio, the modern name for Top 40). If country is your thing, there’s probably a station that plays nothing but that. Same thing for genres like hip-hop/R&B, classical, jazz, and AC (Adult Contemporary, which means old-skewing pop.)

This segmentation of the musical spectrum can be quite helpful to the listener because you know where to go to get exactly the music you want. The melding of music and a station’s brand promise goes back to at least the 1950s when outlets started specializing in providing this new thing called rock’n’roll 24/7 for this new social construct called “teenagers.” (Before the 1950s, no such group existed. You were a kid and then one day you were an adult. The concept of being a teenager began when marketers realized that the boom of new babies immediately following WWII had created a demographic with leisure time, disposable income, and a mind of their own.)

Those early Boomers loved their Elvis, Chuck Berry, and Little Richard. But by the time the Beatles appeared on Ed Sullivan in February 1964, that original rock’n’roll sound had started to sound not just dated but old-fashioned. The concept of rock’n’roll oldies soon took hold and over the next few years, radio stations emerged that played nothing but music from the pre-Beatles era.

Starting in about 1965, “rock’n’roll” had evolved from a form of pop music for kids into “rock,” a serious art form that was not only enjoyed by adults but was also worthy of critical study. And for the next 20 years, rock stations — mostly on FM — proliferated across the continent, with the majority playing a mix of everything from the early Beatles to whatever came out that particular week. The format became known as AOR: Album-Oriented Rock.

But then in about 1980, a shift began. Because the AOR format had been around for a couple of decades, programmers couldn’t help but notice that the music had separated into distinct eras, distinguished by musical style, new instrumentation, recording techniques, and changing social and political views in the lyrics. Realizing that their listening audience had grown older, stations in cities like Cleveland, Chicago, and Houston, started trimming away the amount of new music they played in favour of the biggest rock hits from the 1960s and ’70s. Thus was the term “classic rock” was born.

Commentary:

Why Alan Cross thinks classic rock may be a threat to the music of the future (Jan. 31, 2021)

This aging of playlists worked brilliantly and ratings for classic rock stations soared through the 1980s and 1990s as programmers built playlists from material released before about 1986. Soon, every city on the continent had a station that offered up a steady diet of Led Zeppelin, Rolling Stones, and Pink Floyd. And lo, it was good for the next 20 years.

By the mid-aughts, though, classic rock stations had run into a demographic wall. The Boomers that had kept them afloat were aging out of the demographics prized by advertisers. Even worse, the upper end of the audience was literally dying off. Some painful and risky programming adjustments were necessary.

Two routes were available. First, a classic rock station could rebrand itself as “classic hits,” the new industry euphemism for “oldies.” Playlists were broadened to include enduring pop hits from the 1970s and early 1980s, resulting in new brands like Jack, Bob, and Boom. These stations strove to be the mixtapes of every Boomer’s youth. This is why we hear both The Village People’s YMCA and Stairway to Heaven on the same station.

The second route was to young up the station’s playlist slowly and carefully to keep the average age of the station’s audience within the desirable sales demo, which is ages 25-54. Early Beatles, early Stones, and psychedelic rock from the late ’60s was jettisoned to make room for music that was, well, less old. That means music from the late ’80s and early ’90s.

Herein lies today’s issue with Gen X and their music.

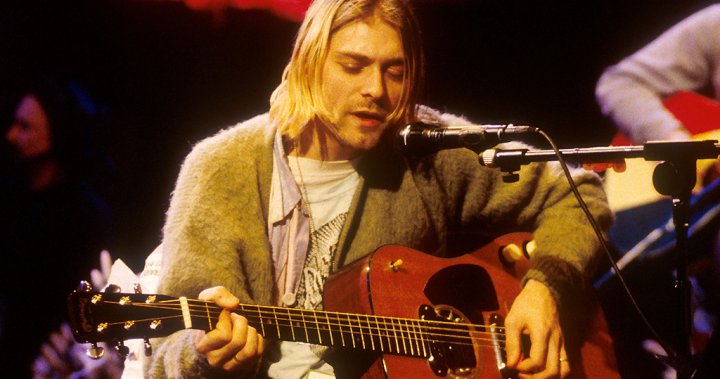

That Simpsons clip was broadcast in the spring of 1996 just after grunge had peaked. Alternative rock, Gen X’s music of choice had taken over and was driving much of popular culture. After years of putting up with the music of the Boomers, Gen X was in charge. Nineties rock — Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Green Day, and dozens of others — was so powerful, so popular, and so good that it has been the foundation of alt-rock culture ever since.

And just like Boomer Homer, Gen X continued to hang on tight to the music of their youth because, well, it was perfect, you know?

But The Byrds, one of those old classic rock bands from the ’60s once put it (quoting Ecclesiastes 3), “to everything there is a season.”

Let’s face it. Smells Like Teen Spirit is an old song. Aug. 27, 2021, will be the 30th anniversary of its release. Pearl Jam’s Ten turns also 30 this summer. In the fall, it’ll be the 30th anniversary of the release of the Chili Peppers’ Blood Sugar Sex Magick. Applying simple math, a 22-year-old into Nevermind today would be like a 22-year-old in 1991 blasting Del Shannon’s Runaway, one of the top songs of 1961 sock hops.

Granted, that’s something of a false equivalency because music evolved so much from that first set of 30 years ago, far more than rock has since 1991. Smells Like Teen Spirit could still be released today and be a hit.

But it doesn’t negate the fact that time marches on, which is why songs Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Green Day, The Offspring, the Chili Peppers, and other ’90s alt-rock hits are now core parts of the library for so many stations formerly branded as classic rock. It’s not uncommon to hear AC/DC’s Shook Me All Night Long roll right into Soundgarden’s Black Hole Sun.

Just as older Boomers are wondering what happened to their classic rock on the radio — even songs like The Beatles’ A Day in the Life isn’t heard nearly as much as it once was — Gen Xers are realizing that the stuff they were moshing to in 1995 is now the new classic rock. Hearing it on a station that played on a station next to the music they set out to destroy a quarter-century ago is a little hard to take.

Last week, I ran a Twitter survey asking if it was time for alternative fans to move on from grunge and the alt-rock of the ’90s. The choices were (a) Yes. It’s time to focus on the new; (b) No. It’s still relevant to this type of rock culture; and (c) Replace it with what?

Of the 1,037 people who cast their opinion in this (decidedly non-scientific) poll, 17 per cent believe it’s time to move on. But 40 per cent are comfortable with keeping that music around. More telling, though, was the 43 per cent who don’t believe there’s any contemporary music good enough to replace it.

And they’ve got a good point. The music industry has done a terrible job of creating new 21st century superstars capable of carrying the torch of those minted in the last four decades of the 20th century. How many rock acts can you name that have emerged since 2000 that are now capable of filling a stadium like days of yore? Go on. I’ll wait.

To be fair, we’re living in a completely different world where the internet has completely destroyed all the old paradigms and conditions that led to rock’n’roll superstardom in the millennium. Instead of today’s generation of young people exclusively listening to their own music (as has been traditionally the case over the decades), their smartphones give them access to 70 million songs. Streaming has conditioned them to focus on individual songs. It’s playlists, not albums. There’s no centre to music anymore. There’s no widespread consensus about what’s good. Everyone is their own music director and they’re choosing to listen to songs from the whole of human history.

All they want are good songs. Streaming encourages consumption by song, not by album, or artist. To today’s 22-year-old, it doesn’t matter if a song is two weeks old or 50 years old. Does it sound great? Then they’ll listen.

Gen X is just going to have to come to terms with the fact that they’re the new classic rock generation. You’ve grown up, kids. Sorry about that.

And before Millennials and Gen Zers get too smug, remember the immortal words of Abe Simpson: “It’ll happen to yoooouuuu!”

—

Alan Cross is a broadcaster with Q107 and 102.1 the Edge and a commentator for Global News.

Subscribe to Alan’s Ongoing History of New Music Podcast now on Apple Podcast or Google Play

© 2021 Global News, a division of Corus Entertainment Inc.