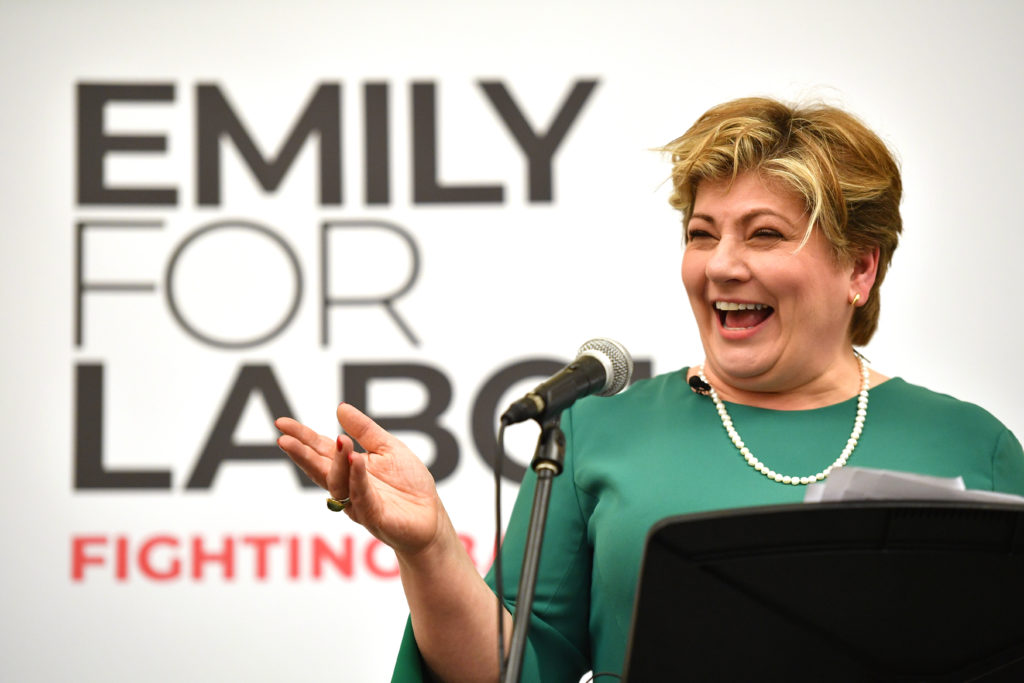

Labour Leadership Contender Emily Thornberry gestures as she speaks on stage during her Leadership Campaign Launch at Guildford Waterside Centre on January 17, 2020. (Leon Neal/Getty Images)

Ask any Twitter user with a red rose and a rainbow flag in their bio and they’ll tell you that Labour shadow foreign secretary and leadership hopeful Emily Thornberry is a gay icon.

Her night spent at historic London gay bar Royal Vauxhall Tavern, rubbing shoulders with tank-topped… boys, with a gin and tonic in one hand and a cigarette in the other, has become the stuff of legend.

And all things considered, Emily Thornberry has all the hallmarks of a woman who gay men would elevate to ‘icon’ status. Emily Thornberry is confident, charming and affable to be around, can deliver a camp one-liner and she’s prime fodder for memes and gifs.

But right now, Emily Thornberry is fighting to make the final ballot to become the next leader of the Labour Party, in quite possibly the party’s most important leadership election in its storied history. December delivered the worst election result for Labour since 1935, a fact Emily Thornberry knows all too well.

The next Labour leader needs to be someone who has the ability to win back power, hold the government to account during one of the most crucial times in the country’s modern history, and they need to be someone who can create a society where all members of the LGBT+ community can live and love with dignity and without fear of discrimination.

It’s the third point in that menu of requirements that we, at PinkNews, have the responsibility of helping you determine.

The first question we asked Emily Thornberry may seem like a simple one on the surface, and it’s one we’ve heard so many politicians give inauthentic answers to: ‘When did fighting for LGBT+ rights become such an integral part of your political agenda?”

Fifteen simple words, but the answer to which separates the true allies from those simply looking to hoover up pink votes.

When we asked Emily Thornberry this question, she gave an answer of epic proportions. We laughed, we cried, it had interwoven narratives, and the shadow foreign secretary – and quite possibly the next leader of the Labour Party – was unstoppable for six minutes.

And this was the first question.

We had no choice but to print that answer in full, and it’s well worth your time to absorb and digest all six minutes of her answer.

But then, we’re only just getting started.

From trans rights and the Gender Recognition Act to a stern message from health secretary Matt Hancock over PrEP; from Kylie Minogue to Boris Johnson; from Dawn Butler being a terrible influence at Pride in London, to building her career as a lawyer defending queer men from police persecution, this is your chance to decide if your rights and your future are safe in the hands of Emily Thornberry.

Well, there we are.

PinkNews: When did fighting for LGBT+ rights become such an integral part of your political agenda?

Emily Thornberry: My younger brother is gay and in the 1980s that was really hard, because it was a time when there was the ‘AIDS gay plague’ when people didn’t want to touch people who were gay, when there was a marginalisation of gay people, and it was really difficult.

My brother was loved very much, and I couldn’t bear the way that he was being treated. He went off to America and he joined this group called ACT UP, which was a group that campaigned to ensure that there was proper treatment for people with AIDS.

It was very, very vocal and did a great deal. He was one of the photographers for them.

A number of his boyfriends died of AIDS. I was in Brighton recently to commemorate World AIDS Day.

They were reading out the names of people who had died. Some of them, the families hadn’t wanted to give the surname but had just given the first name.

Three of the first names were names of people who I knew who had died of AIDS. Before I realised what I was doing – and you’re not supposed to do this as a politician, right? – but before I realised what I was doing, my face was wet and the tears were streaming down my face, as I remembered all of those people that I had known and loved, who had died.

I think that when I first became really into the issue was when my brother came out as gay, but attached to that was all of this victimisation, the whole thing, the fight that was happening in order to be able to save people’s lives, and my brother was an intrical part of that.

He moved to Provincetown, which is a big gay seaside resort at the end of Cape Cod. And we used go there to see my brother and rent one of the family houses on the outskirts of Provincetown.

One of my earliest memories actually, of my daughter and gay rights was, was the [Provincetown] Pride. It started up at the end of town where we were, and so they had all the floats out and everybody had these beads, and because my daughter was a little kid, everyone was throwing the beads at her.

She got so many beads and she was putting them around her neck. After a while she was saying, ‘My neck hurts, mummy. [Laughs] So we had to take these beads off her neck, but we continue to put them on our Christmas tree.

[Laughs] Even now, 20 years later, we put them on the Christmas tree, all the beads from my daughter’s neck.

So I think that’s when it first became an issue – and then as a barrister. There was a time when the Metropolitan Police was absolutely fixated with cottaging.

They used to hang out in cottages, they used to lie on roofs, they used to drill holes in walls of toilet doors and this sort of thing; sit and wait for gay men and then arrest them, and then they’d be taken to court. I basically developed a practice of representing gay men charged with gross indecency.

Basically, what I used to do was just make the jury laugh, because it was so ridiculous.

Here we were at a crown court in front of a jury with a judge and everything else, and they were charged with gross indecency. And it would be the same police officers would always turn up because you had to volunteer for it.

So you get the same police officers again and again, and I remember they would see me coming, and you could hear them saying, ‘Oh, God, I got that b***h again,’ because they knew the way I would be cross-examining them and I would be playing it for laughs.

I would say things like, ‘So, you say he was “masturbating furiously”, could you explain to the jury what that means?’

And of course the police officer would just say, ‘Uhh!’ And I’d say, ‘Well, I’ve got some newspaper here, if I roll it up, would you like to show us?’ Once the jury cracked, once the jury starts to laugh, we knew that they were never going to get convicted.

But it was the only way to deal with this. It was ludicrous that people were being persecuted in this way, it seemed to me, and frankly, it had to be shown up to be ludicrous.

And that’s what we used to do.

I had absolutely no compunction of doing this. And the judges just didn’t know where to look – but you had to do it. You just had to take the mickey.

But there was a serious side.

For example, when there was an increase in muggings on the railway line going up to Bedford, the British Transport Police decided that they had to up their conviction rate because there was pressure on them to get these muggers.

What they did was instead of actually spending their time on the trains arresting muggers, they went into the cottage at [King’s Cross] Saint Pancras, or wherever it was, and they basically just arrested a whole lot of guys for gross indecency – and ruin their lives and gave them criminal convictions – just so they could up their conviction rate, so they could somehow cover up the fact that they weren’t dealing with the muggings.

I mean, this was the world in the 1980s, with a background of AIDS, with people being afraid, and then this huge increase in gross indecency arrests. So yeah, I did my bit.

That was a pretty epic answer.

[Laughs] There were other stories! Should I carry on?

There was another case I did with two police officers. There were two holes in the toilet door, one above and one below, and the police officers were claiming that they had both seen out of this toilet door… so one of them was like standing up and one of them was crouching down below.

And and I remember saying to the police officers, ‘So somebody looked over the toilet door…’

What was going on? I mean, really, you just had to get the jury to laugh and just see ludicrous the whole thing was.

You’ve mentioned the Pride in Provincetown with your daughter and brother, are there any other Pride memories that especially jup out to you?

That was the one that I remember particularly, because it was the one that engaged my kids so much, and my daughter being the princess of the Parade by collecting all of these strings of beads, which was great.

It was lovely, and they always wanted to make sure that when we went on holiday, we went at the same time as the pride parade and Provincetown.

I went last year [to Pride in London] with Dawn Butler, which is a really, really bad idea. Can I just say? Because she behaved so badly, it was all I could do just to get her to behave.

She will claim that I was a bad influence on her – but when she does that, she lies. She was the one who was the bad influence.

We would be going down the parade and people were standing there with a glass of champagne.

Dawn and I were running backwards and forwards and nicking people’s champagne off them and drinking it.

[Laughs] It was very bad behaviour. We got very, very drunk. And then I went back to the back of the parade to see some other people – so I’d already been down it once, drinking people’s champagne on the way down.

And when we went to the back of the parade, people were there, because they knew that I was coming, and they’d bought cans of gin and tonic to give me, which was not what I needed. [Laughs] But that was great.

We’ll have to ask Dawn Butler how much of a bad influence she really is.

You just find out! She’s the bad influence, right? She’s the bad influence?

Everyone knows that Emily Thornberry has frequented the odd gay bar in her time. So, tell us. What’re you ordering at the bar and what song is it going to take to get you down on the dance floor?

I always drink gin. I must admit, I’ll drink beer occasionally, but I like drinking gin. I gave out the result at the [Kylie] Minogue versus [Danni] Mingoue referendum [at London’s Royal Vauxhall Tavern], which was the second Minogue versus Minogue referendum because the first referendum had been so divisive.

We needed to have a second one to bring people together. Anyway, I was the person who read out the results.

Daughter & I home after great night @PushTheButton. Thanku 4 looking after us @thervt. Kylie on 67% – bit like a London Lab MP these days 💅 pic.twitter.com/2R4F5p8KN3

— Emily Thornberry (@EmilyThornberry) July 29, 2017

But I’d been given many, many gin and tonics before I got on the stage. It was fun, but my shoes were too high and there were too many gins, so it was a challenge. But really memorable.

Some of the posters were just wonderful for the the two rival campaigns, drawing the comparison with another referendum that people may remember, and using the same slogans, but tweaking them slightly for Dannii Minogue or for Kylie Minogue.

And what do I dance to? I think maybe I’m a 1970s soul girl at heart. So put on anything like that and I’ll dance to it.

Did you vote in the Minogue versus Minogue referendum?

No! I was the returning officer! I was entirely impartial.

If you had to vote for Kylie or Danni now, who would it be?

It’d be Kylie, come on.

Who is your gay icon?

My brother. I think the struggles that my brother has gone through.

Having seen him go through his journey, and now that he’s a man of his 50 years, one of the things which he says, which is so poignant, is he says, ‘I wasn’t supposed to live this long. I wasn’t supposed to still be here.’

How difficult it is for that generation, having been through everything they have, for all the battles they have fought, and there are still battles going on, but my God, that generation had to fight some battles.

And I think it was a great honour to take over Islington South and Finsbury after Chris Smith, because he’s a guy who fought battles. He was really on the front line. The strength that Chris has shown and the dignity that he’s shown throughout his life has been an example to so many people – he’s a huge role model.

I was thinking when I was on way here, obviously the issue about women is that, only recently, more women have been more open about about being gay, and going through women in history, and thinking who was a lesbian who wasn’t a lesbian… I have a theory about Elizabeth I, I have to say. With all those women at the bed chamber… We know what was happening, really. She was a great role model for everybody, wasn’t she? Whether she was gay or not [Laughs].

Literally as we’re speaking right now, the first same-sex marriage is taking place in Northern Ireland between Robyn Peoples and Sharni Edwards. Do you have a message for the happy couple on this significant day?

I’m incredibly pleased that it’s finally happening in Northern Ireland. My father’s family come from Northern Ireland, and I just didn’t know when this was ever going to happen. The same with abortion.

It just seemed to be impenetrable and whenever any attempt was made to change the law, people would say, ‘Ooh, no, we can’t get in the way of the peace process’, and so on.

It did seem to me that the people of Northern Ireland were way ahead of their politicians, as had happened in the south of Ireland. It was getting ridiculous, wasn’t it?

In the rest of the mainland UK people, same-sex marriage could happen, and it was happening in the south.

So, at long last! It’s happening in Northern Ireland! You know, the idea that people could get married in London and then not be able to be treated as a married couple when they came over to Belfast was just pretty disgraceful in Britain in the 21st century. So, congratulations, and I wish you all the best and all our love to the happy couple.

Arlene Foster, for example, she’s been complaining that same-sex marriage and abortion are both something that’s been imposted on Northern Ireland by Westminster.

I think the DUP represents a certain proportion of Northern Ireland but I actually think that they are getting left behind by the population of Northern Ireland. A

nd I think particularly younger people in Northern Ireland do not recognise the type of Northern Ireland that Arlene Foster claims happens. It may be, with some people, but there is an entirely different generation that have a completely different outlook.

And I’m so pleased that Northern Ireland is catching up with the rest of the 21st century.

You’ve obviously been up and down the country speaking to people in all corners of the UK on the Labour leadership campaign. After doing so, what do you think are the most important issues facing transgendeer people in the UK?

The most resonant time that it came up, I was in Wakefield in this place called the Red Shed.

There was a woman there that I know, because I’ve met her before, and she was asking me questions about trans rights. And then afterwards, she came up and spoke to me and she showed me her wedding photos.

They were lovely, you know, and she’d only recently got married and so on.

But she said, ‘It was so humiliating, look at my lovely husband, but when I married him, I had to say, ‘I take the as my lawfully wedded wife.’

And how humiliating that was for them. And how very difficult you know. You want to have a perfect day when you get married and that kind of central embarrassment was just horrible for them.

People just need to think about the reality of people’s lives in order to get away from the shouting from both sides that you get quite often in this debate. And just think about the people who are caught in the middle.

Why on Earth couldn’t that couple have the sort of marriage that they wanted? What difference does it make to anybody?

It seems to me that these days have got to end and that people should be treated respectfully.

A trans man should be glad to be treated as a trans man, and not to be called a wife. People will talk about it in theory, people will talk about it as a political issue but, in the end, it’s about people. That kind of story is a story for me that begins and ends the issue.

So you backed reforms of the Gender Recognition Act in the past. Is it safe to say you’ll continue to support these reforms?

Yes. Of course.

LGBT-inclusive education, you could say, has been a political football that’s been passed back and forth dating all the way back to Section 28. Thankfully, now, we’re on the verge of it being rolled out. But it’s not been without its difficulties and it’s hard to forget about all those people protesting outside primary schools in Birmingham, simply because youngsters were being taught that some people have two mums and some people have two dads. What did you think of all the aggressive pushback to LGBT-inclusive education?

LGBT-inclusive education is one of those things which I’m glad the government has said they’re going to do something about it, but A, why haven’t done anything about it yet, really?

And B, where is the funding for it?

Where is the assistance being given to teachers so that they do deal with issues in such a way that the frightened 15-year-old feels that they can talk openly for the first time? People do need to have some assistance in order to make sure this is done properly.

We can’t just do this as a gesture, we should be doing this properly. In all our schools in the country, this should be taught, and people should know about it, and kids should be taught about it, because whether or not you or your family disagree with people being gay, you will come across them and you need to understand it.

Frankly, someone in your family may well be gay as well. It’s better for all of us if we have some sort of understanding, and that sort of understanding should be taught in schools, particularly, frankly, if you come from a family where it’s not even discussed.

Bonus question time. The Tories did promise that they would help teachers tackle bullying, including homophobic bullying. So, if a school child calls their gay classmate a ‘tank-topped bum boy’, what do you think their punishment should be?

[Laughs] Language matters on these sorts of things. Language matters.

People can use the wrong word occasionally, with the best will in the world, that is one thing. But to actually slag someone off, to use horrible resonance, disgusting homophobic phrases like that is not acceptable in anyone, let alone the prime minister.

Do you think somebody who uses that phrase is fit to lead the country?

There are many phrases he’s come out with which, I’m afraid in my view, show that he’s not fit to lead the country. Whether it’s homophobic remarks, whether it’s remarks against women, whether it’s remarks against ethnic minorities.

I think that this is a prime minister who is prepared to play many cards in order to divide our communities, and in order to divide off the part that he thinks is going to support him and leave everybody else in the gutter.

It’s a little more than a year since Matt Hancock announced the government had set the target of ending new HIV transmissions in England by 2030, yet queer people are still waiting for a full roll-out of PrEP on the NHS. While our community is still waiting for any movement on this, do you have a message for the health secretary to spur him on?

So as I understand, in order to get PrEP, you have to be on the so-called trials. And the trials are completely oversubscribed with great big waiting lists.

We don’t need trials anymore, we know it works!

Leaving aside the humanity, the morality of this, the whether this is the right thing to do or not – it saves money! If people can be given PrEP then they won’t get HIV and therefore, frankly, there won’t be so much needed to help them when they have HIV through the NHS. So it makes no sense.

It is something that they said they were going to do, they just need to get on and it, don’t they? I mean, I don’t understand it, you know?

You’re either going to do it or you’re not going to do it, so if you say you’re going to do it, then just do it!

Just saying it is not enough, obviously. I just think Matt Hancock will just get on with it if he really means it.

From repeal of Section 28 to civil partnerships and the equalisation of the age of consent, there’s a fair few to choose from, but what do you think is the proudest moment for the Labour Party when it comes to fighting for LGBT+ equality?

There are so many, but I think it takes me back to Lord Chris Smith, and the fact he was the first out member of parliament, and that he was Labour, and that he was supported. And that he was the first of many!

Role models mean a great deal, and he was a great MP and cabinet minister. He really played his part, and continues to play his part, in British politics, and I’m really proud of that.

Do you think the UK would accept an openly LGBT+ prime minister if they were elected today?

I think we’re a little bit of the way off, actually. The truth is we shouldn’t be, but we probably are.

We still have all kinds of issues about what a prime minister ought to look like and who a prime minister ought to be, and there’s so much focus on personality and deconstruction who people are. It shouldn’t be the case, but I think we are quite a long way off.

And lastly, as you’re running for leader of the Labour Party, we may be a way away from a general election just yet, but why should a queer voter support the Labour Party?

LGBT people are as varied as people are. But I think that there’s a commonality of interest between the LGBT+ community and the Labour Party, which is that we are a party of equality and tolerance, and understanding, and not being judgmental.

I think that that is the heart of the Labour Party, and long may it be so. Certainly I think the vision that we have for Britain is probably one which would make the lives of all of us might easier, because there will be greater equality and more trust and more respect.

And it’s not our job as politicians to divide people up and to be judgmental about people, and to say that this person is bad or this person is good or this person is more valuable, or whatever it is, or to or to use disgraceful language or to try to set communities against each other.

I think any politician who does that should never be forgiven. And I would never expect to have anyone like that in the Labour Party, and if we did, they should be out.