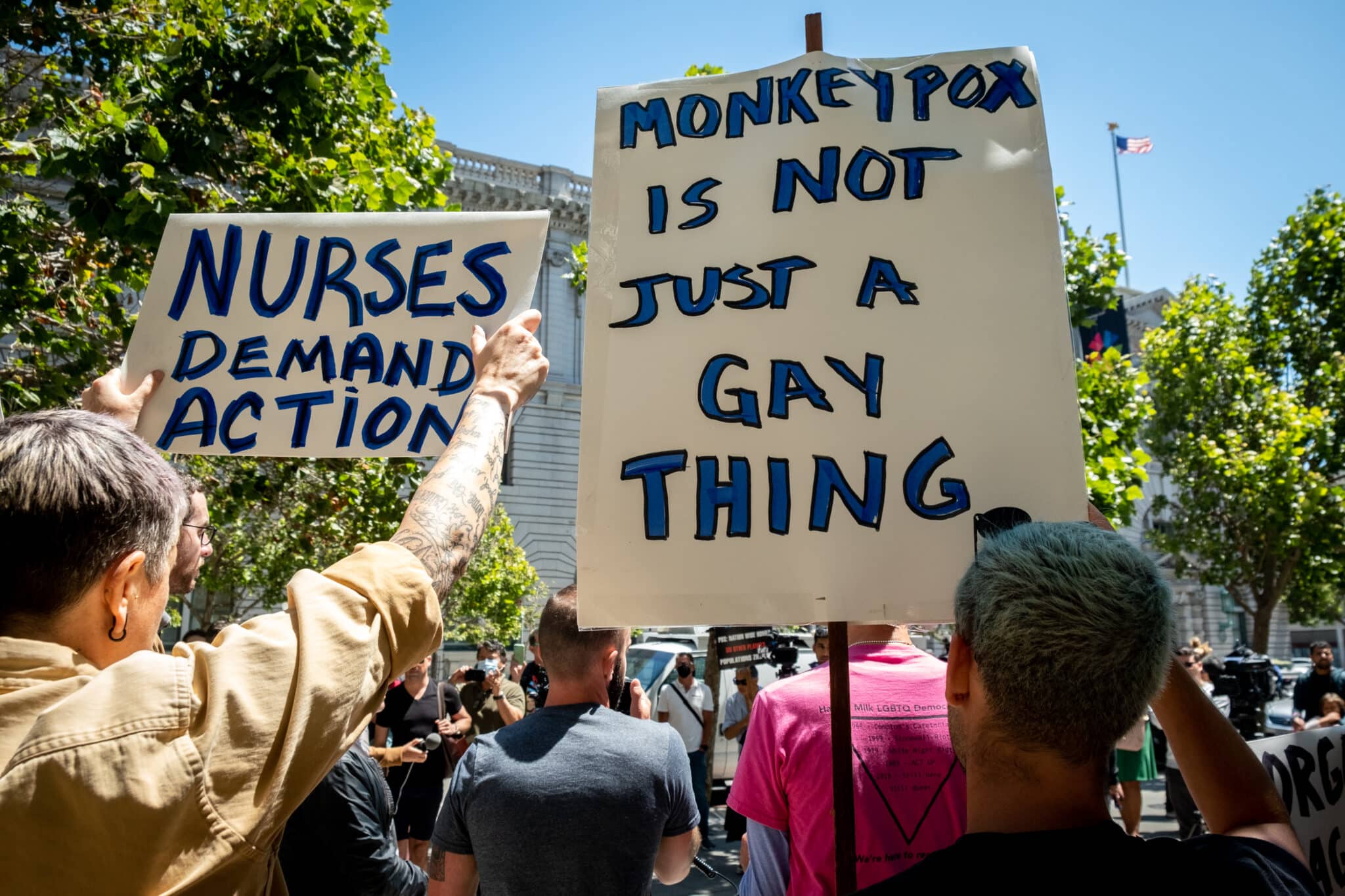

As Americans struggle to obtain the monkeypox vaccine, some queer men are travelling abroad to ensure they’re protected. (Marlena Sloss for The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Some queer men are driving thousands of miles from the US to Canada to get a jab of the monkeypox vaccine.

With cases of the once-rare virus in the US toppling more than 4,600, according to the Centres for Disease Control and Infection, gay and bisexual men continue to be disproportionately impacted.

But the struggle over the limited number of monkeypox vaccines is forcing some people like Seattle, Washington resident Justin Moore to look elsewhere.

Moore told Seattle news outlet KING5 that he and a friend made a two-hour trip to British Colombia in Canada to get their first dose.

Cases in Washington have reached more than 100, state health officials say, 92 of which are in King Country where Seattle is. Due to the “relatively small number of cases”, the Washington State Department of Health has only obtained 400 courses of the two-dose treatment from the federal government.

But only a small pool of people are eligible for the monkeypox vaccine, known as JYNNEOS in the US and as IMVAMUNE in Canada, which is said to work before and after exposure to the virus.

It’s mainly being administered to “high-risk” close contacts of confirmed cases. Healthcare workers on the frontline of the outbreak are next on the list, but the state says the vaccine is “not recommended for the general public” just yet.

This isn’t good enough, Moore said.

“King County health was being very slow with the uptake of access to dosing and communicating in general. It became apparent to me that I was going to have to seek out other places to get it,” he said.

After the “seamless” drive to British Colombia, Moore waited just 15 minutes to receive the vaccine at a local clinic.

In British Colombia, monkeypox vaccines are far more widely available. Any queer person who has had multiple partners, frequents sex spaces, is a sex worker or has had or plans to have anonymous sex can have the first dose.

Moore certainly wasn’t the only one who’s taken the vaccine into his own hands. The Seattle Times reported that Grover Cleveland, 58, made the trip to Canada as well.

As much as he had his doubts about his eligibility, he made the three-hour trip to Vancouver anyway – thankfully, the city’s clinics were more than happy to give the jab to US citizens.

Adam Feinstein also took a trip to Vancouver, a process he said was smooth.

“A lot of people, including myself, have been waiting around with bated breath. When I heard word that there was an opportunity to go to Canada, for me it was a no-brainer. Why wouldn’t I take this opportunity?” he told The Seattle Times.

“We’re having to take public health care into our own hands. It’s my biggest frustration of healthcare here.”

With the US still waiting for millions of vaccine doses, which the federal government says will arrive in the coming months, nearly two dozen states have received fewer than 1,000 doses.

LGBTQ+ activists have slammed the wait-and-see approach adopted by the federal government when it comes to tackling an outbreak afflicting queer men above all.

Getting vaccines to queer men, they said, is an urgent matter. One study found that of 528 monkeypox cases across 16 countries, 98 per cent of patients were gay or bisexual men.

And health experts warn it’s only a matter of time before monkeypox spreads beyond gay and bisexual men.

Yet US health officials have been almost sluggish to do so, lagging behind various European nations that have rolled out targeted vaccination programmes for queer men.

With the World Health Organisation declaring monkeypox to be a global health emergency, LGBTQ+ campaigners feel especially stung by the slow rollout given how the government responded to the AIDS crisis decades ago.

To some, it’s the same-old, same-old of health officials not taking the lives of queer men seriously – and WHO knows this well. The agency has been at pains to stress that monkeypox is not a “gay disease” and homophobia must not be stoked as governments work across the world to curb the virus.

“Stigma and discrimination can be as dangerous as any virus,” said WHO Director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.