Style Points is a weekly column about how fashion intersects with the wider world.

There’s a memorable photo of Dame Vivienne Westwood, her towering platform heels edging their way out of a gilded frame, a painting come to life. It was a promotional stunt for the designer’s Swatch collaboration in 1992—and it feels like the image that most exemplifies her. After Westwood’s passing on Thursday, social media was rife with more traditionally “punk” imagery of Westwood, including the no-underwear ensemble she wore to accept her OBE that same year. That’s fair, given that Westwood is the fashion figure most closely associated with the punk movement. She dressed the Sex Pistols and Bow Wow Wow’s Annabella Lwin during her relationship with both bands’ manager Malcolm McLaren, and brought the music’s DIY spirit to her designs, festooning T-shirts with safety pins and jackets with bondage straps.

But to reduce Westwood to a human anarchy symbol is to do her a disservice. Behind that punk edifice was a woman who knew enough about tradition to shatter it. While questioning empire, Westwood used some of its hallmarks as her building blocks; mixed in with the rebellion, there was reverence. By the ’80s, her references included Old Master paintings, corsets, and crinolines (which she transformed into the notorious “mini-crini”). When I met Westwood in person for the first time, an experience akin to seeing a historical figure pop out of a museum-worthy frame, she immediately identified the dress I was wearing as being inspired by a Frans Hals painting. I soon found that she was more interested in talking about Gainsborough than gossiping about fashion, and that she encouraged design students to copy classic works of art as part of their training.

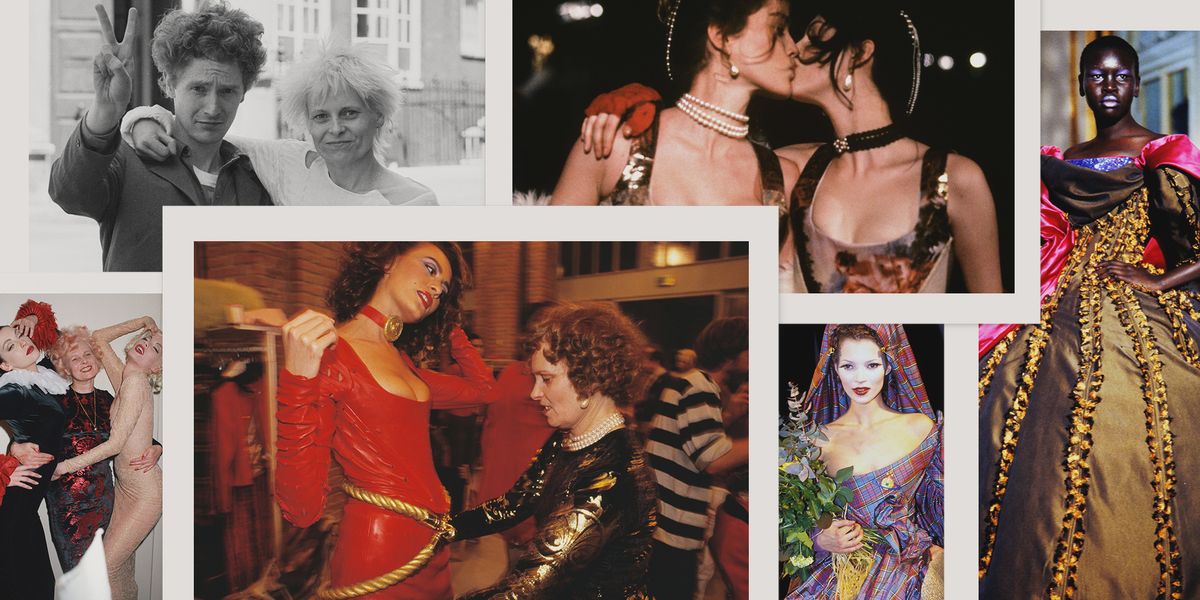

There’s a reason her vintage pieces still go viral, finding fans in Bella Hadid, Dua Lipa, and FKA Twigs. Westwood’s work had almost nothing to do with whatever current trends were crowding the runway, but rather with her own personal obsessions. She was deep in Victorian and Regency fashion while others were pushing bandage dresses. Her collections could be inspired by pirates, witches, dandies, or the heroines of Watteau paintings. She found ways to make even the staidest of British standbys—tartan, Harris tweed, and Sloane Ranger garb—look subversive.

Westwood’s women sported cleavage-spilling, cherubim-flecked corsets or teetered on chopines, but they always looked completely in control. Her supermodel moments were legendary: Carla Bruni went L’Origine du Monde mode in a fur G-string (Westwood would later renounce fur). Kate Moss ate ice cream topless in a tricorn hat. Linda Evangelista swanned around in an 18th-century-style green gown. Naomi Campbell toppled from her sky-high heels, only managing to become more legendary in the process.

Her mastery of tailoring (something she credited to her British background, telling me “I think there’s something in your bones” when you’re an English designer) ensures that her pieces still flatter, shock, and surprise. They feel like pieces of fashion history, but thankfully, not the kind that need to molder behind museum glass.

Perhaps the most punk thing about Westwood was the way she approached fashion and politics. Before the advent of the designer-as-activist, she was warning us about climate change, speaking out against fracking, supporting controversial figures like Julian Assange, and engaging in media-savvy stunts to draw attention to her pet causes. And as the person at the helm of the rare woman-led, independent brand in fashion at the time, she was a feminist inspiration.

But, perhaps in a gesture of English modesty, or one of punk defiance, she was reluctant to accept any of these labels when I asked her about them onstage as she accepted the André Leon Talley Lifetime Achievement Award from SCAD. To borrow the name of one of her legendary store concepts, she was a seditionary to the end. Our industry was one of the many things she refused to take too seriously. As she said that day, “I don’t pretend fashion is some holy thing.”