I tore through my apartment like a junkie, craving my ex’s scent. I couldn’t say exactly what that scent was, only that he—we’ll call him X—had one when he was mine. After five years together, X and I had parted just some months earlier. The possibility of a lingering cologne didn’t feel unrealistic. I came upon a sleeve pressed behind layers of outerwear on the coat rack, and there it was: X’s single-breasted wool overcoat. I brought its lining to my nose; the silk was cold, and its fibers scentless, so I tried it on. Big and boxy, it felt more powerful than my petite, drop-shoulder version. I turned this way and that in front of the mirror, hands in his empty pockets. I styled it with heeled boots and sneakers; with a shoulder purse and without; with the collar down and up, revealing a dapper cobalt underside—this coat was staggeringly versatile!

I’ve been wearing X’s coat almost every day since, pathologically reaching for it when I go to work events, media dinners, and industry parties. I haven’t seen him since he moved out eight months ago, but I still live in the home we built together—between the walls and the cabinets he painted, the furniture he assembled, the photos he took, the dimmer switches he installed, amidst his shoes, his books, and his mail. I live with a ghost.

I’m seeing someone new now. We were going down the elevator one day after he had slid on a roomy sweatshirt of mine. I casually gave the backstory of its gargantuan size—it belonged to a hulking rugby player I used to kiss in college. He went back upstairs and changed. Did he overreact? Or was I the pathological one—some creepy Talented Mr. Ripley cycling through the skins of people, unbothered by the souls they once contained? I decided to take a poll and speak with other women about reclaiming their ex’s clothes—other writers and creatives in media and fashion who, perhaps, had their own stories to tell.

Nina Renata Aron, the author of Good Morning, Destroyer of Men’s Souls: A Memoir of Women, Addiction, and Love, keeps two garments from her ex: A Necros (’80s hardcore punk band) T-shirt and a sweatshirt that says “You are dead” on the front and “Los Angeles Straight Edge” on the back. They’re from a boyfriend with whom, she deadpans to me, “I had such a tempestuous relationship, I had to write a whole book about it.” She used to crave his scent, too. “I’d keep his hair pomade and just huff it all the time. It wasn’t even his. I went out and bought the brand he used.” Her current partner helped her destroy the pomade, along with the rest of his stuff (save the shirt and sweatshirt). Her ex was an addict, and she’d felt she owed it to him to watch over his possessions until he got better. Years passed. He was never coming to retrieve anything. “My new boyfriend, a few times, gently suggested, ‘If you’re ready to get rid of this stuff, I’ll help you,’ and finally we did.”

It brings me back to a conversation I had with the new guy I’m seeing. Late one night, I told him, flat-eyed, that I was living in a haunted house. He thudded on my door a few days later, arms straining full of potted plants and a vibrant bouquet of flowers. “I’m bringing in new life,” he said.

When talking with Aron, another interesting theme surfaced: co-opting cred. “The clothes are such markers of authenticity to anybody who knows about punk’s history, so wearing them feels like borrowing some of the authority that this ex had, the swagger.” It parallels screenwriter Chaconne Martin-Berkowicz’s black cashmere sweater, taken from her first serious boyfriend. “It represented a certain sophistication that I was adopting. Zeke had better taste in clothing than I did. I admired that about him.” The sweater symbolized the beginning of her aesthetic cultivation. “I always trusted Zeke when I was putting together an outfit. I learned to ascertain what looks good and what doesn’t for my body through him.”

While Martin-Berkowicz’s ex shared his tastes and world with her, Aron’s kept her out. For her, there’s satisfaction in claiming something from a group that excluded her. “I always felt kept out of those punk circles. He wielded his power among those people, and so I think I was already determined to change the meaning and make it mine. I was like, ‘This doesn’t belong to those assholes. This belongs to me now.’”

X never gatekept a world from me. What I wanted to leech from him were traits that felt gifted by God. He was good at everything, hyper-capable and deft in a manner that felt superhuman. Cool and unflappable, he had a quiet stillness exemplified by the sound of his voice. Like pours of warm honey, it never went above a whisper. I once took him to the party of a mega-famous actor, and as cameras flashed around us, the celebrity lavished him with compliments on his looks—the health of his hair and the quality of his skin. “Should we take a selfie together?” the actor asked, between adulations. It was a display of whimsy more than anything, yet something that would have gotten me mildly flustered had I been the object of such attention. X looked like he’d just woken from a nap.

While I’m small and half-Asian, X is 6’2” and Scandinavian. I think his stature, his whiteness, and his sheer maleness made me feel more legitimized entering certain spaces. He traveled with me as I reported on a story across Lake Como. Hotel staff would heartily greet him with my last name: “Mr. Mancini! Welcome!” They assumed him to be the journalist coming to visit. And why not? His very build—broad-shouldered and lean, with this unerringly straight tread—radiated authority and elegance. When it came to his athleticism (skilled in everything from riding motorcycles to snowboarding), the sky was the limit. Well, not even. A skydiver, he most recently got his pilot’s license. Then there was the herculean control. We were carrying furniture once, and the corner of this monolithic wardrobe slipped and fell squarely on his toe. Flushing red with pain, X didn’t make a sound; rather, he lifted it back up. “Keep going,” he breathed, bleeding. I was horrified. I was awed.

Our biggest difference: X was never scared, not of the world nor of his own mind. At any given moment, I was thinking about the perils of dying, accidentally stabbing myself in the eye with a knife while chopping, tripping on a curb and knocking my teeth out, or how horrible it would be to get raped. At any given moment, X seemed to be thinking of concepts that structure podcasts—things like innovation, the future of AI, or fusion energy. X embodied everything I lacked, and everything I longed for.

“These relationships do reveal to us our own deeply-held beliefs, about who we are and the supremacy of certain qualities,” Aron reflects. The idea has made me question the dichotomy I’ve created between X and me: his superiority, my inferiority. I recognize an internalized sexism and an internalized racism. And yet, I wear his coat and fantasize about the transference that could occur, if transference were real. What if I, too, could be scared of nothing? An invulnerable machine? I’m not talking about aligning myself with cool styles or groups. I’m talking about his human makeup. What if we could leech the lifeblood we most desired, like vampires?

This idea of subsuming arises in how some women style their ex’s clothes—a signifying of male provenance, yet encased within ultra-femme juxtapositions. “I used to wear it on top of this sparkly mini dress with tights and booties,” says Martin-Berkowicz of her big black sweater. Model and DJ Gilly Chan would pair her ex’s oversized, plaid vintage blazer, from a jazz musician 10 years her senior, with “a tight top or a fancy dress.” Aron only wears her large sweatshirt with a long floral number. “He had many articles of clothing that probably would’ve fit me better. But these things are almost like wearing the fur of an animal you killed,” she says of donning these hard-won trophies—the plunders of a war you survived. It feels just a touch more fanged than borrowing masculinity. It’s eating it and regurgitating a remixed version.

Chan was “20 or 21” when she dated the older musician. “In retrospect, he was probably running away from a lot of internal demons, and being with someone younger was a distraction for him.” When she recalls his plaid blazer, the smell of cigarettes and the taste of martinis come to mind. She kept it “as a memento from this version of myself that no longer exists.” Another woman, who wishes to remain anonymous, also uses her ex’s clothing as a proof point. Her ex-husband’s T-shirts serve as evidence that the eight-year marriage was real. “I was dumped and cheated on. When a bad relationship happens, you protect yourself by not remembering.” The T-shirts serve as evidence she did not simply delete eight years of her life.

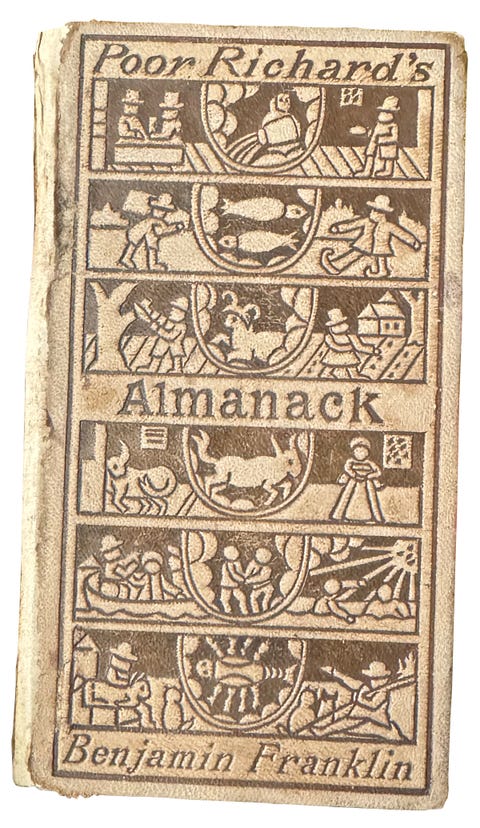

While she possesses nothing from her most formative relationship with a man named Paul, independent creative director Joelle McKenna says, “If I had something of his, I would keep it like a family heirloom. I wouldn’t touch it because I would want to be buried with it.” Wryly smirking at her own melodrama, her sentiment is nonetheless earnest. What she does keep are her “gifts ungiven”: a stamp with a whistle on it (her nickname for him was “P Whistle”), an 1800s copy of Poor Richard’s Almanack, phrases, writing, movies—all items accumulated toward the end of the relationship that she then lost her chance to give. He’s married now, and she wants him to be happy and free. Despite inheriting no material things, she treasures her intangibles. “My sense of humor, trust in the good of humanity, and feeling like there’s magic in the world was informed by that relationship. Paul was a minimalist. He had nothing, and gave me everything.”

The thing about killing someone you love is that, in death, they become saints. We idealize them. “It’s easier to miss someone than love someone,” journalist Eliza Dumais says to me over dinner. With that in mind, and recalling McKenna’s description of Paul, I hear myself describing X—more myth than man. I recall how I once spoke of X to the new guy I’m seeing. “He was Superman,” I said, instantly regretting my word choice.

Michelle Ochs, the creative director of Hervé Léger, is markedly joyful about her ex’s collared shirts—a time machine back to the electric start of her career in New York. “It reminds me of optimism,” she describes. “The world was open. He was starting in his career as a finance guy. I was starting in mine. I remember the energy of the city, getting ready together in the morning, leaving together.” I ask if she still thinks of the shirts as his. Without a beat, she laughs, “They’re mine! It’s become part of my narrative. It’s my story that he was in.” While almost every woman outlines the importance of breathing room with their ex’s things, Ochs sums it up best: “You need the time. You need the space in between to become who you are, to reflect back.”

Sitting with this, I admit I started wearing my ex’s coat too soon. Because I’ve had no interaction with him as a man who’s no longer mine, it’s as if he’s just been on a very long business trip. Perhaps it’s why I haven’t gotten rid of his other stuff. In this other life, he’s still coming home. But people are never frozen where you left them. They move on. The starkest reminder of this is the appearance of a beautiful girl on his otherwise quiet Instagram stories.

Sloane Crosley, who most recently authored the memoir Grief Is for People, makes me chuckle at how un-tortured she is on the topic of her ex’s clothes: “I’m not that weepy about the item!” The item in question is a long-sleeve baseball T-shirt from a guy who worked for The Criterion Collection. “Their softball team was called ‘The True Foes,’” she shares. The graphic: “A sketch of an angry anthropomorphized ball.” She has zero memory of its provenance, “no recollection of stealing it or of it being given to me. It’s just here.” She lightheartedly questions its ownership: “Is it ‘mine’? Or has it just been unwittingly on loan for a decade or two? Who can say?” She’s still friends with the ex in question.

A few weeks later, I sit beside chef Camille Becerra at another dinner. We discuss the point of memoir, the act of returning to things we’re not meant to return to. “At the very least,” she muses, glowing in the candlelight, “it’ll help somebody else.” Several of my closest friends ended their relationships this year, a few more recently than I did. I’d love to say time heals all, and happiness erases sadness, but I’ve come to find the happier I feel in my new relationship, the deeper my grief grows for the man I left behind. Like when you realize a door has been shut for so long, it no longer opens.

I bought a new coat recently, off the street. The day was blindingly sunny, crisp, and cold. Amidst racks of vintage styles, I spotted a brown fur. “Mink,” the salesman explained. It shimmered richly in the afternoon light, like an oil spill. I brushed its sleeve to my cheek, goosebumping at the supple, silky texture. It felt like me in its darkness, its drama, the mild taboo of its material, and the fact that someone probably died in it. Perhaps all the best things are haunted. Perhaps that is the condition of living. McKenna asks me if I “ever commune with X,” explaining how she dialogues with Paul’s memory from time to time. The fact that they’re not physically together is irrelevant. Her question gives my story context—I’ve been communing. Ghosts will always walk among us. Soon, I hope, I can learn to live with mine.