The vibes in Washington—insomuch as vibes can measure the state of the union—are … off. This isn’t necessarily a new development, but as the dawn of a second Trump administration approaches, Dr. David J. Johns, executive director of the National Black Justice Coalition, sounds particularly dubious about the future.

“I was having a visceral reaction to digesting the sense that everything’s on fire for the better part of the last 18 months,” he said during a recent phone interview, which took place before the literal wildfires that have wrought so much destruction in southern California. “People forget that democracies have to be defended by each generation and that education is its midwife.”

Formed in 2003, the NBJC is a policy and civil rights organization that focuses specifically on empowering Black lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer+, and same-gender-loving people in the United States.

“I wish that we would not use the election as such a grounding marker, if only because it distorts the reality that for so many people throughout the country—especially people who are marked by stigma because of their race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation, gender identity or expression or disability status or so many of the other things that shape the lives of Black people—it distorts that these conditions have always existed. And the sense that everything is on fire contributes to people feeling like they are powerless and that there’s nothing they can do, which makes it easy to abdicate the power that people have.”

Insights for the LGBTQ+ community

Subscribe to our briefing for insights into how politics impacts the LGBTQ+ community and more.

“I wish that we would not use the election as such a grounding marker.”

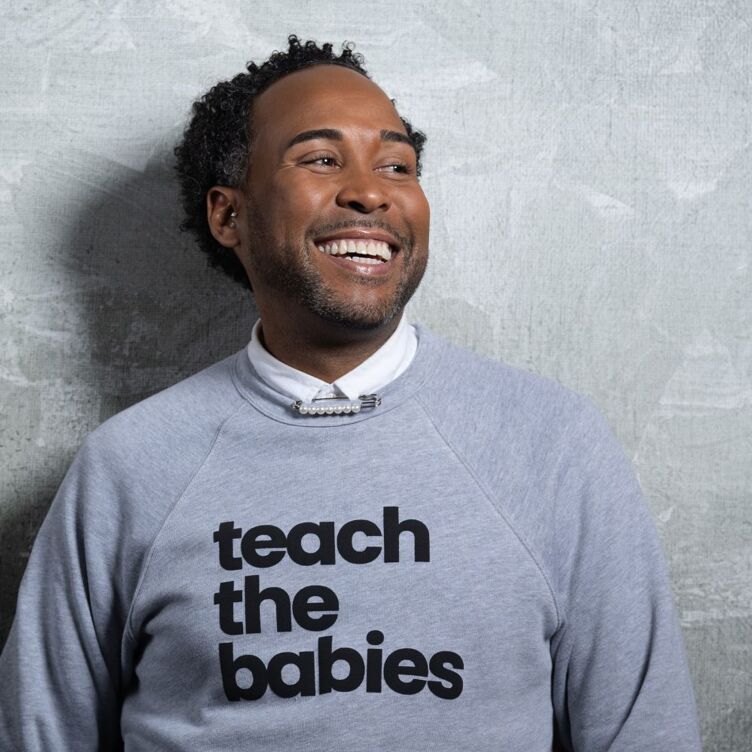

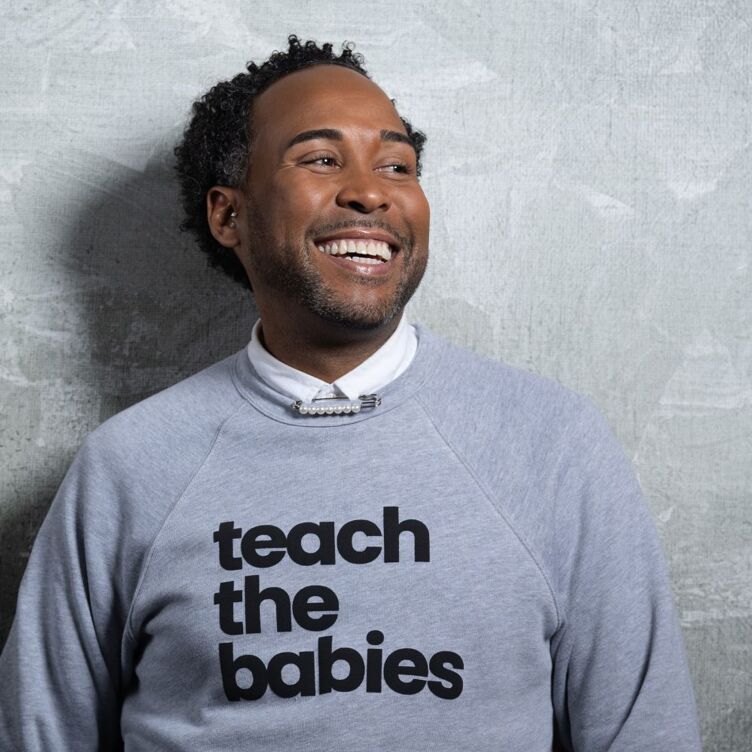

Dr. David Johns, National Black Justice Coalition Executive Director

Black folks have only truly been officially recognized as full participants in American democracy since the adoption of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Efforts to contain, control, minimize, mediate, and titrate Black electoral power did not stop once President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act. Similarly, efforts to entrench housing and educational segregation following the passage of the Fair Housing Act and the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education did not evaporate. The fight to make American democracy and pluralism are better understood as ongoing projects that require intergenerational effort and participation.

As part of his work with NBJC, Johns hosts Teach the Babies, a podcast that looks closely at the Brown v. Board, its aftermath, and its effects on American society. With his background in sociology and education policy (the areas of study in which Johns obtained his PhD from Columbia University), Johns is at home examining and explaining how multiple identities shape the lived experiences of the communities he serves. These days, he is once again turning his gaze to the lessons of previous freedom fighters and educators to build on existing frameworks for survival.

When NBJC surveyed Black communities, oversampling queer Black people about their needs, the organization found that priorities included healthcare, cost of living and its affordability or lack thereof, and that among Black people, significant pluralities, and often outright majorities believe the country should be doing more to support and promote LGBTQ+ rights.

NBJC commissioned the survey in part to ascertain whether Black people are uniquely queerphobic (spoiler: they are not, though intraracial divisions tend to fall along generational fault lines) to inform the organization’s future work. To borrow from Hillary Clinton, Black rights are queer rights, and queer rights are Black rights.

“Culture wars are manufactured to … spur misinformation and disinformation, to have people believing their privilege protects them from the assaults that so many of us have experienced.”

Dr. David Johns, National Black Justice Coalition Executive Director

“Culture wars are manufactured to drive wedges” within coalitions working toward shared progressive goals, Johns said, and to “spur misinformation and disinformation, to have people believing their privilege protects them from the assaults that so many of us have experienced.”

A huge part of NBJC’s policy agenda is focused on housing. The Brookings Institution estimates the United States is experiencing a housing shortage on the order of somewhere between 1.5 to 5.5 million units. Existing at the intersection of multiple stigmatized identities compounds the effects of what is essentially a game of housing musical chairs. So while affordable housing is a challenge for everyone, groups like NBJC work to show policymakers how compounded discriminations like those faced by Black transwomen result in higher rates of homelessness, joblessness, wage theft, deteriorating mental health, and higher suicide rates. Multiple sources of precarity require more creative, elastic, and targeted methods to effectively alleviate them. While that was always the case, Johns is focused on combatting societal effects of anti-Blackness by rediscovering and rekindling traditions of Black affirmation—traditions that include all types of Black people.

“I know that what will allow us to get through is reclaiming African ways of being,” Johns said. “And so much about that is the strength that comes from being in community.” He recommended The Spirit of Intimacy by Burinabe teacher and writer Sobonfu Somé as one of the texts informing this approach, also namechecking the intellectual work of Fannie Lou Hamer, Paulo Freire, Martin Luther King Jr., Bayard Rustin, Pauli Murray, and bell hooks as guiding lights.

Related:

In recent years, the far right has aimed its cannons at attacking Americans who are gender nonconforming, who complicate the assumed and enforced narrative of a rigid gender binary. Johns thinks we could all take a page from Somé in embracing and acknowledging gender nonconforming people as those who have found liberatory fulfillment within an existence characterized by liminality by seeking and celebrating the fuzziness of straddling worlds, communities, and identities.

“Somé says the words gay and lesbian do not exist in the village, but there is the word ‘gatekeeper,’ ” Johns explained. “Gatekeepers are people who live a life at the edge between two worlds, the world of the village and the world of the spirit. … The way that gatekeepers are able to do their jobs is simply because of strong spiritual connection and their ability to direct their sexual energy, not to other people but to spirit. They stand on the threshold of the gender line. They are mediators between the two genders. Gatekeepers do not take sides. They simply act as the sword of truth and integrity.”

MAGA fascism remixes Jim Crow authoritarianism with xenophobia, antisemitism, and the moral and sexual panic of McCarthyism. It thrives on a blinkered individualism that counts “do your own research” as its rallying cry, embracing the might of terrorism as its enforcement mechanism. It engineers a false sense of unity through the creation of a common enemy (anyone whose identities would place them under the umbrella of “woke” or “DEI,” its adopted terms of derision). It is a politic of isolation, dissatisfaction, and demagoguery. But it is not new, nor is it insurmountable.

The most effective methods for subverting its power and its violence, Johns asserts, are the classics, especially those embodied by the “gatekeepers” Somé identifies, including community, mutual aid, doing away with colonialist ideas that “access to anything is based on a state-sanctioned relationship between heterosexual people.”

To navigate and survive a new age of polluted information systems delivered to us by tech princelings who see themselves as masters of the internet, Johns is revisiting and rekindling the lessons of bell hooks espoused in Teaching Critical Thinking: Practical Wisdom. As he attempts to anticipate further attacks on civil rights and liberties and craft strategies for making it through a period of neo-apartheid, Johns is reading Peter Fritzsche’s Hitler’s First Hundred Days: When Germans Embraced the Third Reich.

“Part of what I’m getting from this book is the importance of continuing to have uncomfortable conversations so we can work through the discomfort in ways that allow more of us to actually survive,” Johns said. “It’s also affirming for me the importance of helping people tell stories to shape moments when we might be able to in the future, move policy.”

Related:

Johns is clear-eyed about the dangers the future may hold, even when just saying them aloud highlights the precarity many fearfully anticipate. Steeling himself with the wisdoms of previous leaders is coupled with “doing as much as I can to make sure that my community is prepared to support my fiance in the event that I am indicted or arrested or jailed or experience any of the things that I know so many people who exist in the world in the ways in which I do have experienced,” Johns said.

Johns has found access behind the velvet ropes of electoral or corporate power in his work with NBJC and in previous policy roles in Congress and the White House when the balance of power was less hostile. He’s continuing to encourage high-placed allies and accomplices to the mission of equal rights to redouble their commitments to diversity, equity, and inclusion, to think about and center the morality of their decisions rather than their short-term political expediency.

But more than anything, Johns keeps coming back to the basics: investing in and shoring up community and a commitment to seeking and sharing truth, especially through stories.

“If we don’t do this better together, then we all suffer the consequences, and so many of us will die,” Johns warned. “… We have better odds of surviving this hunger game if we all go together. And so my hope is that that lesson from our ancestors would be a compelling one.”

Related:

Native Son 101

A celebration of queer and gay Black men who have made an impact this year.

Subscribe to the LGBTQ Nation newsletter and be the first to know about the latest headlines shaping LGBTQ+ communities worldwide.

Don’t forget to share:

This article includes links that may result in a small affiliate share for purchased products, which helps support independent LGBTQ+ media.